The donkey is stereotypically bumbling, slow, and stubborn; the elephant- big and clumsy. Being compared to one of these animals is not exactly flattering in this sense. Yet, for well over a century, they have been the popular symbols of America’s major political parties – the donkey for Democrats and the elephant for Republicans. So how did the donkey and elephant enter into our political lexicon? As one could imagine, it all started with an insult.

The donkey is stereotypically bumbling, slow, and stubborn; the elephant- big and clumsy. Being compared to one of these animals is not exactly flattering in this sense. Yet, for well over a century, they have been the popular symbols of America’s major political parties – the donkey for Democrats and the elephant for Republicans. So how did the donkey and elephant enter into our political lexicon? As one could imagine, it all started with an insult.

The 1828 presidential election between Republican (not to be confused with the modern Republican Party which was formed a few decades later) John Quincy Adams and Democrat Andrew Jackson is still considered one of the dirtiest campaigns ever run in American politics. Jackson and his supporters called Adams corrupt, spoiled, and a “libertine” – someone who lacked moral restraint, usually in reference to sexual matters.

Adams supporters attacked Jackson’s military record; his violent temper; his disrespect for authority; and most unfairly, his wife for marrying Jackson before she was “properly” divorced. (Earlier Jackson killed a man for issuing this same insult.) They also called Jackson a “jackass” – comparing him to a stubborn, dumb donkey. Jackson was famously known as a populist and his slogan, “let the people rule,” reinforced this. Republicans claimed that if the people ruled, it would be a bunch of jackasses ruling the country.

But Andrew Jackson, the savvy politician he was, turned the jackass into a positive symbol. He pointed out the virtues of being a “jackass” in campaign addresses: persistence, loyalty, and the ability to carry a heavy load. It also symbolized humble origins and simplistic virtues, an ode to the common man. This helped Jackson further differentiate himself from the aristocratic Adams. Jackson wanted to be the president of choice for every day citizens.

He soon put the donkey on his campaign posters and referenced it in speeches. Jackson continued to be associated with a donkey even after his presidency when an 1837 political cartoon depicted him attempting to lead a donkey who refused to follow. This was to show that the Democratic party (the donkey) would not be lead by the previous president (Jackson). From here, the donkey only made rare appearances as the symbol for Democrats until later in the century.

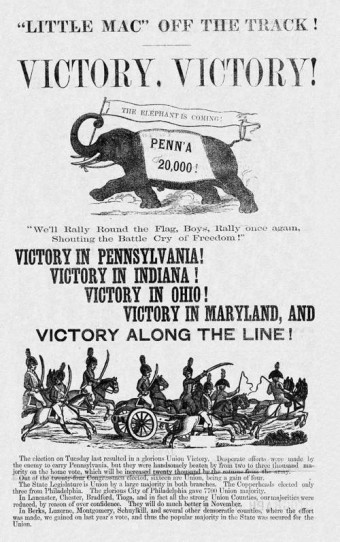

The elephant as the Republican symbol (now referring to the modern Republican Party) first made an appearance during the 1864 presidential election in a pro-Lincoln newspaper Father Abraham. (Really it was more political propaganda than “news”paper- though of course the same could be said for a large percentage of news outlets throughout history and even today when it comes to matters of politics.) Father Abraham depicted an elephant carrying a banner and celebrating Union victories in the war. At the time, the well-known slang phrase “seeing the elephant” meant to engage in combat.

The elephant as the Republican symbol (now referring to the modern Republican Party) first made an appearance during the 1864 presidential election in a pro-Lincoln newspaper Father Abraham. (Really it was more political propaganda than “news”paper- though of course the same could be said for a large percentage of news outlets throughout history and even today when it comes to matters of politics.) Father Abraham depicted an elephant carrying a banner and celebrating Union victories in the war. At the time, the well-known slang phrase “seeing the elephant” meant to engage in combat.

So how did these two animals go from here to popularly representing the Democrats and the Republicans? This is thanks to famed political cartoonist Thomas Nast.

Nast started becoming famous with the onset of the Civil War in 1861. He was working for Harper’s Weekly at the time and illustrated over 55 engravings of battles and war scenes. In December of 1862, Nast debuted his version of Santa Claus, the jolly old fat man in a red suit we now know today. Prior to Nast’s depiction of Saint Nick, he was always shown as more of a religious figure and much less jolly.

Later in the political arena, he called out Boss Tweed’s political machine, helped get Ulysses Grant elected president, and brought to light the savagery of the Ku Klux Klan’s campaigns against African-Americans. He also, as mentioned, popularized the donkey as the symbol for the Democrats and the elephant as the Republican symbol.

In a cartoon called “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion” that ran in an 1870 issue of Harper’s Weekly, he used the donkey to represent the “Copperhead Democrats” – a faction of Northern Democrats that were in opposition of the Civil War. In it a donkey is kicking a dead lion, who was a stand-in for the recently deceased Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Nast thought Copperhead Democrats were anti-Union and believed the press’ treatment of Stanton was disrespectful.

In a cartoon called “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion” that ran in an 1870 issue of Harper’s Weekly, he used the donkey to represent the “Copperhead Democrats” – a faction of Northern Democrats that were in opposition of the Civil War. In it a donkey is kicking a dead lion, who was a stand-in for the recently deceased Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Nast thought Copperhead Democrats were anti-Union and believed the press’ treatment of Stanton was disrespectful.

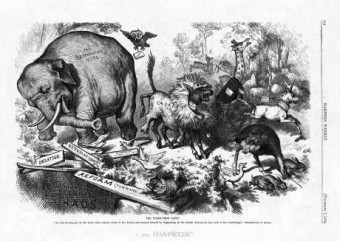

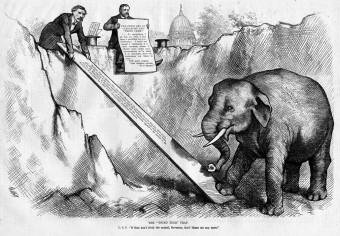

In 1871, the Republican elephant made another appearance, this time in a Nast cartoon in Harper’s Weekly, to remind Republicans that their intra-party fighting could cause them to lose the election. The 1874 cartoon entitled “Third Term Panic” really solidified the symbolism for both animals.

Ulysses S. Grant (whom Nast was a supporter and good friend of) had been president for two terms, elected in 1868 and again in 1872, and was contemplating a run for a third term. (It wouldn’t be until 1951 and the 22nd amendment that a term limit was placed on the presidency, thanks in no small part to FDR’s four term run as president.) The New York Herald very much opposed Grant’s potential run and wrote several articles complaining of “Caesarism” – meaning military or imperial dictatorship.

In “Third Term Panic,” it shows a donkey wearing the skin of lion, with “Caesarism” emblazoned on it, scaring off other animals, including a wobbly, unbalanced elephant, labeled as “the Republican vote,” about to fall into a pit (labeled inflation and chaos).

In “Third Term Panic,” it shows a donkey wearing the skin of lion, with “Caesarism” emblazoned on it, scaring off other animals, including a wobbly, unbalanced elephant, labeled as “the Republican vote,” about to fall into a pit (labeled inflation and chaos).

Though Grant didn’t end up running, Nast’s cartoon didn’t do enough to prevent the Herald’s “Caesarism” claims from working. The Republicans ended up losing the control of the House in the election and Nast showed his disappointment with another cartoon in November of that year – an elephant caught in trap that was set by a donkey.

Thanks to Nast, by 1880 the donkey and elephant became the accepted symbols used by other political cartoonists and writers for the two political parties and the association has stuck around since.

Thanks to Nast, by 1880 the donkey and elephant became the accepted symbols used by other political cartoonists and writers for the two political parties and the association has stuck around since.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy:

- The Origin of the Red State/Blue State Dichotomy

- The Difference Between a Donkey and a Mule

- Interesting Facts About Every U.S. President

- Do Elephants Really Have Good Memories?

- The Origins of the United States Democratic Party and the Republican Party

Bonus Facts:

- Thomas Nast was a functional illiterate. He couldn’t read or write, which probably explained why he drew pictures and could connect with others so well through his drawings. As his cartoons progressed, they began to incorporate words, which were written in by his editor or wife. In fact, when he was first married, he had his wife read to him while he drew. Later in life, when he had more money, he hired scholars to read to him from science, physics, and history books, as well as Shakespeare and Twain.

- Writer Albert Boime wrote in the American Art Journal that “as a political cartoonist, Thomas Nast wielded more influence than any other artist of the nineteenth century… his impact on American public life was formidable enough to profoundly affect the outcome of every presidential election during the period 1864 to 1884.” Not bad for an illiterate person.

- Besides the aforementioned Santa Claus depiction we know today and the elephant / donkey association, Nast’s legacy includes popularizing the “Abe-Lincoln” look of Uncle Sam and popularizing “Columbia,” the iconic image of America as a woman.

Expand for References

- Why are a donkey and an elephant the symbols of the Democratic and Republican Parties? – HowStuffWorks

- How Did the Donkey & Elephant Become Political Mascots? – Mental Floss

- Why Are Democrats Represented as Donkeys and Republicans as Elephants? – Access2Knowledge.org

- The Donkey and the Elephant – OurWhiteHouse.org

- Andrew Jackson: An American President – PBS

- How the Jackass Became a Democrat – Colorado Central Magazine

- Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age By John William Ward

- Thomas Nast The Power of One Person’s Wood Engravings – historybuff.org

- Thomas Nast and French Art by Albert Boime

- Thomas Nast – Wikipedia

- Caesarism – Freedictionary.com

The post How a Donkey and an Elephant Came to Represent Democrats and Republicans appeared first on Today I Found Out.

How a Donkey and an Elephant Came to Represent Democrats and Republicans

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento